Lincoln Cent Has Other Fans

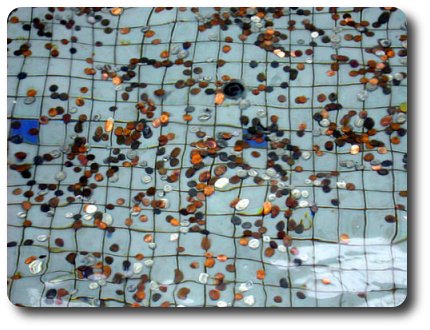

It packs so little value that merry kids chuck them into the fountain near the candy store just to watch them splash and sink. Stray pennies turn up everywhere: in streets, cars, sofas, beaches, even landfills with the rest of the garbage.

A penny bought a loaf of bread in early America, but it’s a loafer of a coin in an age of inflation and affluence, slowly sliding into monetary obsolescence.

For the first time, the U.S. Mint has said pennies are costing more than 1 cent to make this year, thanks to higher metal prices.

“The penny is going to disappear soon unless something changes in the economics of commodities,” says Robert Hoge, an expert on North American coins at The American Numismatic Society.

The very idea of spending 1.2 cents to put 1 cent into play strikes many people as “faintly ridiculous,” says Jeff Gore of Elkton, Md., founder of a little group called Citizens for Retiring the Penny.

And yet, while its profile of Abe Lincoln marks time in the bottom of drawers and ashtrays, the penny somehow carries a reassuring symbolism that Americans hesitate to forsake.

“I know it’s just a cent, but still it would seem odd not to have the Lincoln and the penny around,” said Jennifer Bishop, 37, of Pleasanton.

Gallup polling has shown that two-thirds of Americans want to keep the penny coin. There’s even a pro-penny lobby called Americans for Common Cents.

The Mint’s announcement is a milestone, though, because coins have historically cost less to produce than the face value paid by receiving banks. They are moneymakers for the government.

U.S. Rep. Jim Kolbe, R-Ariz., wants to keep it that way. But when he asked Congress to phase out the penny five years ago, he failed; he intends to try again this year. If he fails again, he joked recently, he may open a business melting down pennies to resell the metal.

The idea of a penniless society began to gain currency in 1989 with a bill in Congress to round off purchases to the nearest nickel. It was dropped, but the General Accounting Office in a 1996 report unceremoniously acknowledged that some people consider the penny a “nuisance coin.”

In 2002, Gallup polling found that 58 percent of Americans stash pennies in piggy banks, jars, drawers and the like instead of spending them like other coins. Some people eventually redeem them at banks or coin-counting machines, but 2 percent admit to just plain throwing pennies out.

“The idea of phasing out the penny is a good call,” said Bill Souza, proprietor of Souza’s Liquors in Oakland. “Pennies are not taken seriously anymore. They’re a pain to deal with. I say that both as a private citizen and as a retailer.

“I was recently in New York City and all the vendors in Times Square have all their merchandise rounded out to the nearest dollar, nickel or quarter,” he said. “It’s time to get rid of the penny because it’s not valued.”

Then there’s Adam Lavine, chief executive of FunMobility in Livermore, who said he didn’t “like the idea of the economy done in units of five. There is something unlucky about that.”

“Yesterday I was taking my 5-year-old daughter to the fountain in San Ramon where she threw in 10 pennies. We have an emotional and cultural attachment to pennies,” Lavine noted.

Respect for pennies is another matter.

“When I see a penny on the ground now, I don’t even bother picking it up,” said John Mitchell, 62, of Dublin. “They’re practically worthless.”

Others have their own reasons for valuing the humble coin, which borrowed its colloquial name from British currency. The “cent” — meaning 1 percent of a dollar — has been struck every year except 1815, when the United States ran out of British-made penny blanks in the wake of the War of 1812.

“I look up to Lincoln and what he stood for, and that’s why I think it’s disrespectful to throw pennies away,” said Sarah Deberardinis, 47, of South San Francisco. “I respect the penny because I respect Lincoln.”

The penny took on the profile of President Lincoln, beloved as the Union’s savior during the Civil War, on the centennial of his birth in 1909. The first ones carried ears of wheat on the tails side, but the Lincoln memorial has replaced those. Four new tails designs with themes from Lincoln’s life are planned for 2009, with a fifth permanent one afterward to summarize his legacy.

This redesign, the first major one since 1959, has heartened penny lovers.

Another problem is deciding what to make the penny from. Copper, bronze and zinc have been used, even steel in 1943 when copper was desperately needed for the World War II effort. In 1982, zinc replaced most of the penny’s copper to save money, but rising zinc prices are now bedeviling the penny again.

Those who want to keep the penny coin include small merchants who prefer cash transactions, contractors who help supply pennies and consumer advocates who fear rounding up of purchases.

“We think the penny is important as a hedge to inflation,” says director Mark Weller of Americans for Common Cents. “Any time you have more accurate pricing, consumers benefit.”

Like shouts in a playground, pennies can multiply quickly.

Just ask Edmond Knowles of Flomaton, Ala., who hoarded pennies for nearly four decades. He ended up with more than 1.3 million of them — 4.5 tons — in several drums in his garage. His years of collecting brought him about $1 a day — $13,084.59 in all.

Staff writers Francine Brevetti, David Morrill and Allison Louie contributed to this report.

(via insidebayarea.com)